About One Health for HEAL

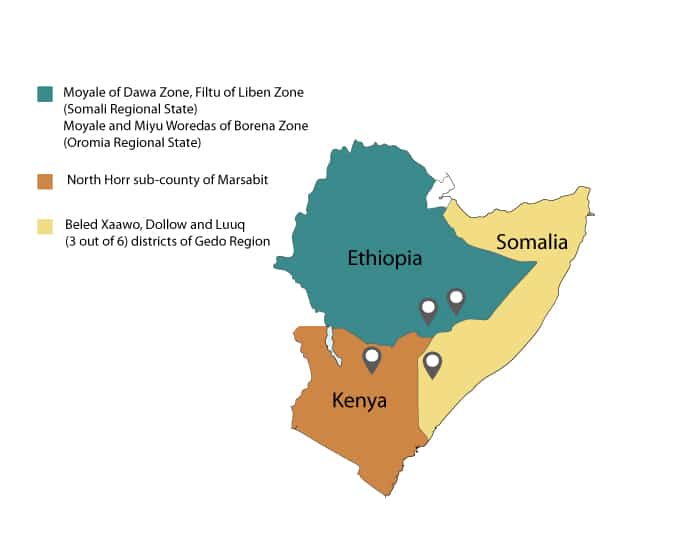

The One Health for Humans, Environment, Animals and Livelihoods (HEAL) program applies a One Health approach to enhance the well-being and resilience of vulnerable communities in pastoralist and agro-pastoralist areas of Ethiopia, Somalia and Kenya.

These countries share similar climate, population dynamics, challenges, strong cross-border interactions. They also hold strong cultural and historical links.

The HEAL program brings together professionals in human and animal health and the environment to achieve better access to human and veterinary health services and sustainable natural resources management.

One Health is an intersectoral approach recognizing the close connection of the health of people to the health of animals and our shared environment. Compared to single sector approaches One Health results in an added value of health and wellbeing of humans, animals and ecosystem including rangelands, financial savings, and sustained services.

To operationalize One Health on the ground, the HEAL program works at three levels: with the communities, with public and private service providers, and at the policy and wider socio-economic level.

HEAL operational areas

Phase 1 (2020-2024)

In its four-year phase 1, the HEAL program aims to enhance well-being and resilience to shocks of vulnerable communities in pastoralist and agro-pastoralist areas in the Horn of Africa.

1. Engage pastoral communities in defining sustainable, demand-driven and need-based One Health units

To achieve this, the program carries out the following activities:

- Maintaining and reinforcing the multi-stakeholder innovation platforms (MSIPs) in each intervention kebele/villages, reinforcing a consensus-building process among local authorities and community consultations and engaging through MSIPs on needs and scope of OHUs.

- Developing, monitoring and adapting participatory rangeland management plans using tools aligned with a OH approach, work with community members (MSIPs) to develop OH interventions that integrate seasonal and spatial distribution of human and animal diseases and rangeland management plans and maintain a suitable people-centred digital platform for the collection, timely sharing and participatory interpretation of relevant OH data. Moreover, it will promote the use of existing microfinance and insurance products to facilitate access to OHUs, identify gaps and opportunities for the scale-up phase of the program, support and promote livelihoods diversification to support the resilience of communities and support certification of rangeland units and revision and/or direct implementation of management plans.

2. Operationalise context specific and cost-effective OH service delivery models

HEAL will achieve this objective by carrying out the following activities:

1. Preparing detailed plans for gender sensitive OHUs, in terms of both infrastructures and mode of operating. This involves:

- Preparing, planning, and managing static or mobile OHUs in target sites

- Setting up infrastructure and equipping static or mobile OHUs

- reparing a gender-sensitive manual on how to operate OHU, including health, natural resource management services

- eveloping interactive gender sensitive OH training modules for different stakeholders (frontline service providers)

- Promoting increased participation of women in OHUs

- Training OHU staff (training of trainers) on how to plan interventions at the multi-sectoral level and facilitate timely intervention, training on OH, zoonoses, animal health and husbandry, NRM, gender integration and on integrated planning and response systems and management

2. Operating different types of One Health Units

The specific activities include:

- Running and supporting the delivery of services through OHUs with on the job training, backstopping and supervision

- Conducting community awareness-raising and training at village level (WASH, human health, livestock health, nutrition, antimicrobial use, natural resource management and gender)

- Supporting the establishment of households’ and community latrines

- Identifying, testing and piloting appropriate ICT strategies (mobile apps/platforms) for human and livestock disease identification and surveillance, rangeland health reporting, conflict and disease warning

3. Scaling operations at district level

The activities to be carried out include:

- Supporting the development of a district/sub-county plan for the scaling up of OHUs in new sites

- Identifying financial and technical resources for the operationalization of the district/sub-county plan

- Preparing a monitoring plan to support the proper running and support of services through OHUs

- Training district concerned authorities in the management and monitoring of the OHUs plan

- Supporting communication structures across rangeland units and developing strategies to sustainably fund such initiatives

- Conducting assessment and evidence gathering studies as needed for new areas

3. Ensure that policy makers and investors recognise HEAL-OHUs as solution for service delivery for pastoralist communities in the Horn of Africa

To achieve this objective, HEAL will execute the following activities:

1. Documenting evidence and lessons learnt

- Documenting and measuring progress indicators and outputs of OHUs by assessing and analysing feasibility, viability, and social cost-benefit of static and mobile OHUs

- Conducting evaluation assessment of OHUs in target communities

- Documenting available digital tools for early warning and surveillance and documenting needs for credit proposal

2. Coordinating with JOHI and other One Health programs and government initiatives relevant to HEAL

- Conducting joint seminars with Jigjiga University and its Institute of Pastoral and Agro-Pastoral Development Studies in the framework of the JOHI to share experiences

- Supporting/hosting student programs in HEAL intervention areas

- Engaging and participating in meetings and workshops of other One Health initiatives to share results and promote HEAL

- Liaising with regional and national coordination platforms and other country programs to avoid duplication of activities and foster synergies in the region

3. Regional community of practice for One Health for development

- Implementing a communication strategy to engage with One Health and other relevant initiatives (research and implementation) in the region, to promote a process of learning and innovation

- Maintaining and reinforcing the digital platform for HEAL community of practice on OH service delivery

- Organising online seminars, workshops and contributing to OH-related conferences

- Disseminating evidence on best practices to get the buy-in of other donors and policymakers

HEAL value proposition

Potential development impact

HEAL builds the capacities of vulnerable pastoralist communities, services providers and regional institutions to ensure needs-based services provision.

Bottom-up approach

HEAL brings a participatory approach to applying One Health by ensuring that vulnerable communities, service providers and governmental institutions participate in every stage of the program, from problem identification to implementing solutions and managing the end-of-program handover of responsibilities and processes. Multi stakeholder innovation platforms support communities to develop sustainable, gender-sensitive strategies for coping with threats, especially environmental threats related to climate change.

Regional approach

The mobility of pastoralist communities requires solutions that are not limited to a defined geographical area. HEAL’s regional approach covers border areas of Ethiopia, Somalia and Kenya, offering the comparative advantage of reaching communities, regardless of their current location, who move across regional and national boundaries.

Rationale

The rationale for the HEAL program is underpinned by the very fact that opportunities for better engaging with governments on the provision of appropriate basic service for pastoral communities exist. Nonetheless, the process of building capacity and enabling environment for appropriate service provision is long and complex in any community, and is particularly difficult among pastoral people, given their levels of poverty and a policy environment that does not fully support the dynamics of their livelihood systems. Yet, until pastoral citizens develop the skills and confidence to define and defend their vision for their development and appropriate service provision, they will remain vulnerable to others’ interpretations of what is best for them.

Helping pastoralists (both as individuals and as members of community-managed platforms, such as the Pastoral Field Schools and Multi-Stakeholder Platforms) to understand the dynamics of their own livelihood system in relation to external policy processes and ongoing institutional reforms is an essential pre-requisite for building capacity and enabling environment for appropriate service provision. Improving their knowledge will help them to identify their own solutions to current problems and speak in an informed and authoritative manner on policy issues of concern to them, especially in relation to service provision. The ability to use the “language” of policymakers will give them a more equal footing in discussions with the government and the development community, as well as the confidence to change outsiders’ perceptions of appropriate service provision. Pastoral people need to familiarize themselves with the policy process and put themselves at the centre of the local and national debates aimed at addressing their priorities and needs.

For instance, in Ethiopia, the HEAL program coincides with the launch of a major national One Health strategy, and the proposed approach is expected to demonstrate best practices and optimum implementation of One Health in the underserved and vulnerable pastoral areas. Besides, the current trend of policy processes shows that countries in the HoA (e.g., Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia) support the One Health approach as an effective means to transform the institutional environment in an acceptable and appropriate manner for pastoral development and service provision. In this light, HEAL builds on already existing initiatives by supporting a participatory, context-specific, coordinated and integrated approach to service delivery in the form of One Health units with a robust objective to sustainably strengthen human, livestock and environmental health. Eventually, this approach will encourage communities to develop sustainable strategies for coping with changing environments and threats related to climate change. To this effect, the HEAL program is designed to coordinate efforts and to establish commitments around the One Health approach by integrating One Health Units into local, national and regional health policies.

HEAL is designed to promote and facilitate innovation platforms which include multiple stakeholders to allow learning and change, problems diagnosing, identification of opportunities and ways to achieve the desired goal, namely an adequate and appropriate institutional enabling environment to support service provision. These multi-stakeholder innovation platforms (MSP) target men and women from local communities, leaders of pastoral civil society groups, program staff of NGOs and other development organizations, policymakers including government and donors at local, regional and national levels, researchers, MPs, and other key actors from the public and private sectors. The objective is to ensure that by the end of Phase 1 of the program not only are beneficiary communities, decision-makers, key actors from the public and private sectors, and practitioners more knowledgeable about the application of One Health, but they are also better equipped to argue the case for the application of the One Health approach on the basis of information and evidence facilitated by HEAL in the program locations. Overall, the MSPs will help identify the needs of the pastoralists and design the types of services that respond to their needs in a more effective manner.

Past phases

Inception phase

In an 18 month inception phase in 2019/2020 the HEAL program laid the foundation to establish One Health units. MSPs were established to engage communities in the process and a series of assessments were conducted in preparation of Phase 1.

1. One Health policy context

A desk review on the One Health policy context of Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia mapped the gaps and needs on matters related to the operationalization of OH in the governments’ service delivery systems. The key areas covered in the review include:

- Major zoonotic disease threats

- Status and threats to the natural ecosystem

- Establishment of the One Health systems in the country – history and current situation

- Existing national policies and strategies related to One Health

- One Health initiatives

- Gaps and needs in the establishment/institutionalization of One Health

The study provided evidence to support the coordinated efforts around the OH approach through the refinement of the concept of One Health Units (OHUs), aligning it to the policy priorities of the three countries and facilitating its implementation through the integration of OHUs into local and regional policies related to human, livestock and environmental health service delivery.

Ethiopia and Kenya have established OH strategic plans which are currently at various stages of implementation by the governments’ structures, with extensive support from non-governmental organizations (NGOs) through national and regional initiatives. Somalia does not have a OH strategy in place yet, but there are NGO-supported initiatives that support the institutionalization of the OH in the government structures, despite the challenging political environment.

Key policy gaps and needs to be addressed in the region were as follows:

- Governance and management: There are no specific OH government policies to support OH despite interest at national and international levels and efforts to establish OH platforms and enact strategies. Kenya and Ethiopia have national OH strategies in place. Though there are still challenges in acquiring government funding to implement them and reliance on donor funding and external support.

- Network and partnerships: There are inadequate multi-sectoral working mechanisms across the three countries to respond to disease outbreaks and other OH related hazards. This is primarily due to poor information sharing and communication across the relevant sectors. In Somalia, the added challenge of having three administrative zones (Puntland, Somaliland and South Central) poorly collaborating in political issues further exacerbates the poor coordination mechanisms for multisectoral communication and response to any disaster. In general, across the 3 countries, there is very low to zero involvement of the environmental sector in relevant national OH initiatives.

- One Health capacity development: There are efforts in Kenya and Ethiopia to government employees in the humans, animals and environment sectors and to enhance the tertiary education with a common OH curriculum across all key disciplines. This is through the Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Program which are is spearheaded by the Ministries of Health and Livestock/Agriculture. This is missing in Somalia as the strategies developed to support human resource improvement has not been implemented.

- Surveillance, preparedness and response: There are efforts in the three countries to establish and strengthen disease surveillance, early warning, preparedness and response systems from the national to the lowest administrative level, though there is poor inter-sectoral information sharing. This hinders the quick implementation of effective joint response mechanisms.

- Communication and advocacy: Overall, there is clear evidence of poor communication and coordination across sectors primarily due to lacking strategies and guidelines for multi-sectoral collaboration. There are existing communication and exchange platforms for the OH stakeholders but only at the national or county/regional level in Kenya and Ethiopia. Limited communication and coordination are observed at the lower district level, where disease surveillance and management should take place.

- Operational research: There are existing transdisciplinary research activities providing evidence to foster multidisciplinary approaches in responding to emerging global and national health challenges and influencing policy. However, these are mainly implemented by non-governmental organizations and research institutions with the involvement of government institutions.

- Monitoring and evaluation: The lack of a centralized verifiable data source for existing surveillance, monitoring and response systems and any other information related to OH in the relevant government ministries hinder the proper evaluation of the institutionalization of the OH approach.

2. One Health vulnerability and capacity needs assessment

A key activity of the inception phase was the vulneratibliy and capacity needs assessment in target areas, which incorporated socio-economic and gender analyses.

The aim was to:

- evaluate the health status and main health problem of the pastoralist communities and their livestock

- identify the most vulnerable groups in the community, practices of men and women related to the management of human and animal health/diseases

- review the availability and accessibility of health services, availability of drug and supplies, in both the health and veterinary systems

- evaluate the geographical, traditional, and other barriers preventing pastoralists to access the existing healthcare/veterinary facilities.

The assessment provided evidence on the needs of the system and community level (provider side and consumer side). These findings will feed into the standard operating procedures, the training plan and the investment plan of the OHUs that are being developed during the inception phase. The assessment covered the following themes:

- National level: assessing the capacity needs at the national and regional level of the relevant government ministries and developing recommendations tailored to the specific needs of the countries

- Community level: gaps in access to human and animal health services and needs of vulnerable pastoralist communities and recommendations to address these

- Human and animal health service providers (public, private, traditional): capacity gaps in private and public service provision identified in the service delivery system, HR, infrastructure, equipment and recommendations to improve capacity and service delivery in the targeted areas

3. Livestock migration routes and natural resource management

HEAL conducted workshops with local stakeholders on Participatory Rangeland Management (PRM) and Livestock Routes Mapping (LRM) to understand gaps in integrating human and livestock health services within the rangeland management activities. The exercise was based on the existence or the creation of rangeland units. Rangeland units often cover large areas that are used by certain community groups and these units often do not follow woreda, zone or regional borders. PRM mapping had previously been conducted in Borana zone for Gomole, Melbe, Dirre, Golbo, and half of Wayama rangeland units. The consultation highlighted that local conflicts affects management of rangelands and communities need support in certification and enforcement of the rangeland plans.

In the Somali region, in both Moyale and Filtu woredas, the preliminary evaluation indicated the absence of well-delineated rangeland units. Therefore, the program identified, mapped and validated these units. In phase 1, HEAL will focus on supporting activities from the identification and establishment of Rangeland Units to certifying the rangelands. Capacity building will be provided to the management committees to ensure smooth integration of planning and execution of activities between the human-animal health and rangeland sectors.

When mapping the livestock routes and available human and animal health care system along these routes, clear gaps in infrastructures and services were documented. The proximity of the rangeland units to the border and the low capacity to control the spread of infectious diseases was another major concern, together with contraband trade and grazing mobility. The rangeland units identified and mapped during the PRM process by HEAL lack animal health services and infrastructures and the existing human health post needs facilities and drugs to continue to support the community.

In Somalia, the mapping activity was done through the two HEAL MSIPs in Tullow Amin village of Bullahawa district and Surgudud village of Dollow district. In both sites, the developed maps have been validated by the communities and presented to the local administration.

Based on the gaps and challenges identified in the inception phase, HEAL phase 1 aims to:

- Liaise with relevant government bodies to respect the legal holding rights of the people to the resources in the rangeland units and follow the Gomole certification process.

- Conduct community-level awareness raising assessment on rangeland units and human/animal health.

- Facilitate participatory land-use planning which guides the development of rangeland management plans leading to certification. Participatory land demarcation shall be planned to resolve the Woyama case through discussions between the Garri and Borana communities and government bodies

Livestock route mapping

Livestock route mapping (LRM) workshops were organised to identify and map the livestock mobility routes in the HEAL intervention areas, identify locations of water points, markets, animal health posts and major rangelands and to check their functionality. Mapping workshops were held in Moyale, Borana and Filtu areas facilitated by geographic information systems (GIS) and natural resource management (NRM) experts. The mapping processes in the three sites were able to engage several participants from diverse backgrounds to locate the infrastructures on the topographic maps manually. The produced maps were digitized and georeferenced for future use and will be updated with chances in services and infrastructure in the HEAL sites. This information helps to establish links between PRM and human and animal health. Additional insights from disease distribution patterns (geographic and seasonal) will be overlaid with these maps to strengthen the integration of animal and human health with the environmental components of HEAL.

4. Anthropological research in Kenya and Somalia

An anthropological study was conducted in the HEAL program area of Somalia as the last exercise of a long-term anthropological study carried out across Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia from 2015-2019. The aim was to understand perceptions, needs and behaviours of local pastoral communities towards human and animal health and their strategies of adaptation to the environment, also in relation to climate change.

The research carried out in Somalia employed an innovative methodology to address the limited accessibility and mobility within the country, given security concerns. Following the approach used by journalists in hostile zones, data collection was done through a stringer/spotter relationship on the ground and information reported daily to the principal investigator at the central level who trained, guided and monitored all field-activities. A local researcher with a public health background (the stringer) was recruited and trained to collect the information from local communities, through five Household Spotting Units (HSU) composed of members from the same family in each of the different ecosystems identified in the program area. The research was conducted through three main phases: remote training of the stringer by the anthropologist then the stringer held meetings with the local authorities in the field and selected the 5 HSU and lastly the activation and maintenance of the data flow, from the HSU to the stringer and from the stringer to the research operator. Information and data retrieved on the ground were enriched and validated with extensive literature research.

The study area was identified within the Gedo Region of Southern Somalia, one of the pilot zones of the HEAL program inception phase. To reduce the extension of fieldwork in relation to timeframe and security, the study area was limited to the triangle with vertexes in Dollow, Luuq and Beledxaawo, district capitals and entry/exit points in/out Somalia due to their strategic position with Ethiopia (Dollow), Kenya (Beledxaawo) and central Somalia (Luuq). The following five ecosystems and relative settlements were identified within the study area and became the focus of the research:

- Lowlands (seminomadic pastoralism): Malkariyey, Beledxaawo District

- Highlands (nomadic pastoralism): Sullale, Luuq District

- River and alluvial plains (agriculture and mixed economy): Bantaal, Dollow District

- Small towns and peri-urban belts (services, markets, modernity): Tuulo Amin, Beledxaawo District

- Internally displaced people camps (totally artificial and alien to surrounding livelihoods): Kabasa, Dollow District

The key issues emerged from the research include:

The northern Gedo Region is characterized by change, change in clan composition, increase in population density (variable with the continuous in- and out-flows of IDPs), constraints against nomadism (security), diminution in herd size, shift from camels to sheep and goats and change in urbanization patterns (in and out camps and refugia).

Change is evident also in the environment surrounding the pastoral communities. Throughout the field activities, pastoralists rumoured about a lack of nutritional power in some fodder plants and the depletion of grazing land. An environment-related issue is the infestation of algarroba (Prosopis juliflora), a problem shared by other pastoral communities in the region. The plant, looking like an acacia, was imported from Brazil for reforestation programs. Now it is infesting by encroaching the land, impeding the passage of animals and people and preventing livestock to feed on the grass under it. Its pods and leaves do not give nourishment although fed by livestock. Its thorns are infective, so much that a camel can die by foot necrosis if pricked.

In terms of human health, common cold and dengue are the most reported diseases among local communities. As already reported across local communities in Ethiopia, religious leaders and sheiks play a key role in the management of illness and they are often the first actors to consult when someone in the family is sick. That is why any health program should involve religious leaders in the public health chain.

Regarding animal health, local pastoralists agree on the importance of treating some common diseases at all costs, such as for example Contagious Caprine Pleuropneumonia. On the contrary, killing livestock diseases (like anthrax and meningitis) are perceived as “from the old days” and “eradicated”. Animal diseases are mainly believed as “imported” by migrants and improper livestock management during transhumance (overcrowding, mixing and poor control).

Finally, concerning the environment, all respondents seem not to perceive climatic change as a crisis, but rather as a temporary variation in season pattern, a weather phenomenon the pastoralists are well acquainted with. Besides previous knowledge about climate uncertainty, religion comes in: there is not much to do against Allah’s will about floods and droughts. This somehow contrasts with the mantra encountered and repeated throughout all research locations that ‘environmental problems are manmade’. Agriculturalists seem more knowledgeable about soil destruction, while pastoralists are predictably mainly worried by fluctuations in rainfall.

Supporting Partners